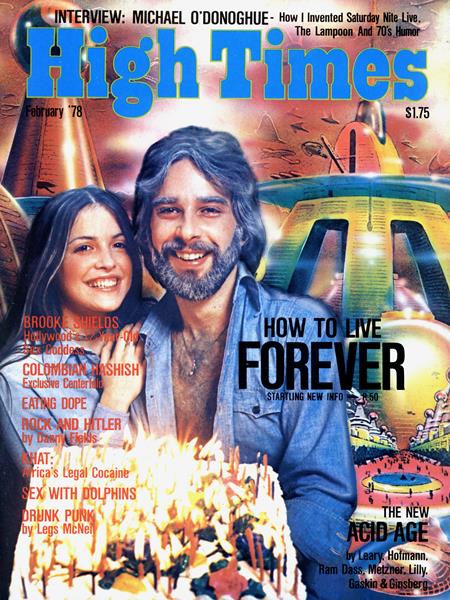

By A. Craig Copetas and Gary Putka

Khat: the cocaine of Africa—the mint green leaf of the shrub Catha edulis—is a way of life in the new nation of Djibouti and the ancient land of Yemen. Grown on large farms resembling old-world tea plantations in Ethiopia’s rainy and embattled southeastern Harrar Province, its rough, bushy plant also thrives in the cool mountains of Yemen, where glossy-eyed Arabs ruminate its invigorating leaf like so many campesinos chewing coca.

After cultivation and harvest, branches of leaves are rushed to Diredawa, Ethiopia’s civil-war-torn transportation hub, for the night flight to clients across the Djibouti frontier. In Yemen the precious crop comes down from the mountains the quickest way possible, for the khat leaf is perishable and must remain fresh or lose its potency. It’s efficacy after cutting lasts for roughly 24 hours, and then only if the leaves are kept moist.

Not even the Somali-led insurgency in southeast Ethiopia has interrupted the rapid transshipment from Diredawa to Djibouti. The khat run has been a twice-daily affair on Ethiopian Airlines. It is so lucrative that African observers are confident it will continue unhindered even if the Somalians win the siege of Diredawa. Meanwhile, the cargo is increasing daily and stands presently at eight tons a day. When khat arrives in Djibouti, the normally listless tropical port explodes into a bustling metropolis.

By late morning, motorbikes, trucks and cars carrying wholesale traders make the three-mile speedway dash to the airport to buy up the natural stimulant by the bag as soon as it is offloaded.

Although khat has been illegal in Djibouti ever since the country gained its independence in 1976, the newly-vested authorities have followed the colonial French example of looking the other way. Indeed, using the tactics employed by the Americans in Vietnam, France tacitly encouraged the chewing to keep the natives quiet. In the century of French occupation, the use of khat in the former territory of the Afars and Issas grew from an occasional diversion for a few Issas tribesmen to a national pastime for the male population.

Today French soldiers are on hand at Djibouti’s airport to help the importers carry away the prize goods for street auction. Buyers flock around the sunsheltered stalls to bid for bags. In less than 20 minutes the airport is empty again, as buyers rush back to town. The first to return is thought to have the freshest load to offer retailers, who sell khat from mini-stands or stalls throughout the city.

Women, according to tradition, abstain from chewing khat because they don’t like the taste. Men of all ages start their daily dreams at noon, after the airport rush, when the stuff is readily available on the street.

The khat habit puts some families in a bind, as a bunch costs nine French francs ($2), a third of a day’s wages for most laborers. There are many unemployed in the new nation, but the chewing tradition hasn’t changed, so such purchases impose a hardship on the poor families who make up most of the khat-consuming population in the tiny republic.

In turn, khat provides a relief for the unemployed, helping them forget their troubles. To sit all afternoon chewing khat until the sun goes down at dinnertime is as common in Djibouti as decadent café life in Paris.

Chewing takes place only after the user selects the good leaves and casts off the undesirable ones with the stems. As with coca, the mastication process slowly takes place as the wad of leaves is alternately chomped and swished around until it dissolves and a new supply is needed. Most chewers prefer to use only one cheek for their khat, causing a sort of national epidemic of “hamster” facial malformations. Khat also colors teeth a yellowish green.

Coca-Cola or Pepsi is sipped along with the hr outage, for the combination of caffeine and khat makes an exciting high. In addition, users like to smoke contraband American cigarettes with their afternoons of fun and forgetting.

Khat has been classified by the French Narcotics Bureau in the B category (marijuana has the same classification), meaning that possession can be subject to fine or jail. The stimulant is legal in the United States, but climatic conditions in most of the country do not favor its cultivation. As no formal studies of khat have ever been made, long-term effects of its use are not known.

The new government in Djibouti, under President Hassan Gouled, has hinted that it would take measures against the khat traffic. Government ministers, however, have had their own special loads of leaf flown to them at conferences in other parts of Africa and Europe.

Just across the border in Ethiopia, growers are happy their produce is still a cherished item in Djibouti, for without the foreign buyers they would be hard-put to find a new market. Only a small amount is chewed in Ethiopia, and the government is not too happy about the profitable crop. Peasants devote huge acreages to khat, depleting land needed for vital food crops.

In the past, fresh leaves were transported by train, but a group of rebels blew up a bridge on the strategic railway between Djibouti and Ethiopia in June 1977, and the line has not been repaired. So now the air run is the only practical route to convey fresh khat to Djibouti. Nomads sometimes traverse the desert border by night in illegal camel caravans that arrive the next morning with small loads.

Last year Ethiopia exported 1,400 tons of khat by air, which represents more than a quarter of Djibouti’s foreign agricultural imports, listed at 5,400 tons annually. No one knows how many tons of leaf reach the new republic clandestinely.

The khat scene in the Yemeni capital of Sana is similar to Djibouti’s, but with several picturesque and debilitating differences. Unlike Djibouti, Sana has special khat houses, seedy cafés or inns found off the sidewalk, where users may take their daily doses while puffing on water pipes and drinking cola for more soothing kicks. You can buy khat over the counter in these funduks and even chew all night with lodgings at your disposal for the total lull.

The situation is more intense in Sana because khat chewing has engulfed the town with funduks, enticing users to so cialize with other chewers and communi cate with the madhar (water pipe) that replaces the American cigarette used in Djibouti. The inns encourage more inten sive and numerous uses of khat, but the biggest reason why users outnumber their kind in lJjibouti is that a bunch of leaves costs about half as much. Yemen, directly across the straits of Bab a! Mandeb from Ethiopia and Djibouti, grows its own khat bushes in a similar climate, but there is no foreign commerce in the leaf.

The bushes grow in the mountains where the famous mocha coffee once thrived. But the coffee is slowly disappearing because Yemeni farmers have decided to concentrate on the profitable, easy-to-care-for khat, planting seedlings as soon as a row is plowed.

Because khat can be cut easily and is sold quickly on a daily basis, business is booming. As soon as the crops are cut. baskets come down from the mountains, sometimes in cars, jeeps or trucks, sometimes on muleback, to be sold in the open market and at street stalls or in specialty shops that sell nothing else. Farmers usually deliver the crop directly, and they must pay a fixed “khat tax.” according to the weight of a load entering Sana.

As in Djibouti, it’s a mad rush to town before noon to catch the first customers with the freshest batches, wrapped in husks to keep them moist. Yemenis stop work promptly at 12:00. rush to the nearest market and buy their daily needs. The stalls and shops are only open for 12 to 14 hours for the quick sales of leaves cut in fields early that morning.

Khat time in Yemen is midday to midnight. People rush home to chew their troubles away or share them at the local funduk. Because of this tradition, nothing is open after noon, and even offices close down until the following morning.

Everyone chews—workers, policemen, soldiers, bureaucrats and merchants. In Sana there is even a minority of women who indulge, a rare instance of nondiscrimination in the sexist Arab world. The government that came to power in 1974 would like Yemenis to kick the habit and transform plantations back to fruit and coffee crops, something which may be physically impossible to do because the land has been ravaged by so many years of khat growing.

Khat was once a social problem for the neighboring People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen), the only Marxist Arab state, but the government outlawed it. However, users in South Yemen so far have had no need to fear any legal reprisals. Although khat is forbidden there, it is tolerated.

In northern Somalia, which has a climate like neighboring Ethiopia, some khat is grown but there are few chewers. Djibouti, Yemen and Ethiopia are the only countries in the world where significant amounts of khat are consumed, posing a sociological problem for the Horn of Africa, now in the throes of violent military problems. As the military situation worsens, some top officials are pleased to ignore the favorite pastime of euphoric citizens, and an increasing number are glad to join them for the traditional, allday high.

Read the full issue here.