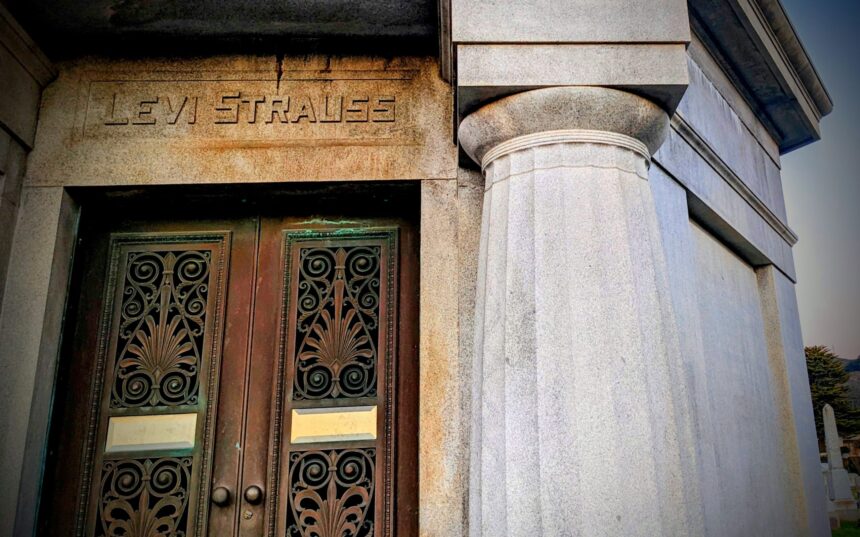

Entirely by chance, my father is buried just a few rows away from Levi Strauss, the man whose name is synonymous with denim and one of the most enduring clothing brands in American history.

For decades, whenever I went to the cemetery just outside San Francisco, I’d quickly pause to say hello to Mr. Strauss. And I always made it a point to tell him, “Thanks for the jeans.” It was kind of our thing.

Aside from a few stray words, I seldom speak out loud if I’m by myself, even when I’m hanging out with dead people. That’s why it surprised me when, one afternoon, my relationship with Mr. Strauss took an admittedly unusual turn.

Instead of a pause on my way in, I made a hard stop. I’d just been through a difficult stretch in my work as a product developer and was reeling. Seeing that I had the ear of a fellow inventor, I decided to open up to Mr. Strauss that day, and I could tell he was a good listener. It was the first real conversation we’d ever had, and it taught me more than I could have imagined. I never talk shop when I’m visiting my father—he was a podiatrist.

Taking a moment to read the room before discussing my business in polite company, I looked around the mausoleum to where Mr. Strauss now resides and found the information I was searching for etched in white marble: LEVI STRAUSS — BORN 1829 – DIED 1902.

Seeing that he wouldn’t have even known about the earthquake—let alone all of the political matters I was about to discuss—I realized there was a lot I should catch him up on first.

Hemp Before the Fall

I told Mr. Strauss that I worked in the cannabis industry—except that he would know it as hemp. It was a crop grown everywhere in the nation, commonly used to make durable fabrics, canvas, and rope. Hemp had been indispensable during the Gold Rush, especially in a maritime city like San Francisco, as its fibers could withstand saltwater without breaking down.

But in 1906, shortly after Mr. Strauss passed away, a new law required medicines to disclose their ingredients on labels, and hemp was suddenly listed alongside narcotics like opiates and cocaine. Over time, they were clumsily lumped into the same category and wrongly classified as poison. But it isn’t a poison. And to this day, not a single death has ever been reported from its use.

Even so, U.S. cannabis prohibition officially took root in 1937—a chapter of history rarely acknowledged, and one I knew would interest Mr. Strauss especially. I explained how hemp had been rebranded as “marihuana” in the 1930s, a slang word in Spanish intentionally chosen to make the plant sound foreign and threatening rather than a simple, one-syllable crop. Behind the scenes, however, that “threat” wasn’t cultural—it was personal.

The Earliest Days of the Drug War

Publisher William Randolph Hearst, whom Mr. Strauss surely would have known personally, had a substantial investment in the timber industry, which supplied wood pulp for his newspapers. But hemp-processing equipment was quickly advancing to make the crop a cheaper, stronger, and more sustainable alternative to wood, which put Hearst’s empire at risk.

With an agenda to eliminate the competition, Hearst’s newspapers ran sensational headlines designed to stoke fear and turn public opinion against the plant.

In a coordinated media campaign with the newly formed U.S. Bureau of Narcotics, hemp was portrayed as a dangerous drug tied to crime and immigration—deemed a direct threat to the nation.

In 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act made hemp illegal in the United States, setting a global precedent and essentially wiping out a crop that could have supplied countless innovations over the years—including compostable plastics, biofuel, and important medicines—all because one man wanted to safeguard his timber business. Imagine that.

Strangest of all, those federal restrictions remain unchanged in the United States, nearly a century later.

Today, cannabis continues to be listed alongside heroin as a Schedule I drug—the most dangerous category under federal law.

By contrast, cocaine and methamphetamines are Schedule II, as is fentanyl, which killed nearly 50,000 Americans last year. In other words, cocaine and fentanyl are legally considered less dangerous than cannabis, despite zero deaths. And that’s a blatant contradiction I can’t unsee.

But the narrative wasn’t new to me; it echoed the 1970s and ’80s, when I was growing up and cannabis was treated like a weapon in America’s culture wars. The White House taught everyone to “Just Say No,” while police officers came into 75% of the nation’s classrooms through the D.A.R.E. program to warn us that marijuana was the gateway to everything evil and that anyone who used it was destined to ruin their lives.

That made things confusing when I accidentally caught my mother smoking pot—and it broke my heart. I couldn’t speak a word to her for weeks.

At the same time, alcohol not only got a free pass but was celebrated at every turn. Looking back now, the most destructive and dangerous things I’ve witnessed didn’t come from cannabis but from people who drank too much alcohol. And I could no longer unsee that one, either.

Fifty States, a Thousand Contradictions

I told Mr. Strauss how, eventually, states and counties began creating their own laws. More than 40 states and territories have legalized medical cannabis, and nearly half allow recreational use, too. But it’s not as straightforward as it sounds.

California was the first state to legalize medical use in 1996 and added recreational use later, yet 53% of its jurisdictions still ban any type of cannabis business.

In New Orleans, cannabis is sold from what look like ice-cream trucks, because only mobile dispensaries are permitted there, but not brick-and-mortar ones.

And in our nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., the rules are especially odd: dispensaries abound, but buying and selling is still illegal, so it’s given away as a “free gift.” Buy a $50 lighter and choose your cannabis gift; spend $75 for the same lighter and get a top-shelf selection.

Despite the patchwork of laws, legal cannabis still felt revolutionary. For the first time, I knew in advance which effects I’d experience with each plant strain and began integrating it into my yoga and meditation practice to reset my nervous system from PTSD. It did wonders for me, and I’m truly grateful to have lawful access.

Prospectors and Pickaxes

I explained how those experiences—and even Mr. Strauss himself—had inspired me to bring my specialized skill set to the supply chain. “You see,” I said, “I studied the old Gold Rush to understand the new one and was reminded that the people who prospered most weren’t the miners, but the merchants who sold them pickaxes, shovels, and jeans. And after years of saying hello to you, the point finally landed—so that’s where I decided to focus my attention. I would let someone else deal with the weird regulations. I’m going after the supply chain where I can do business anywhere in the world without restrictions.”

It was then that I decided to ask Mr. Strauss for some business advice. How had he done it—and found his way during the first Gold Rush? And what would he do moving forward if he were standing in my very same boots?

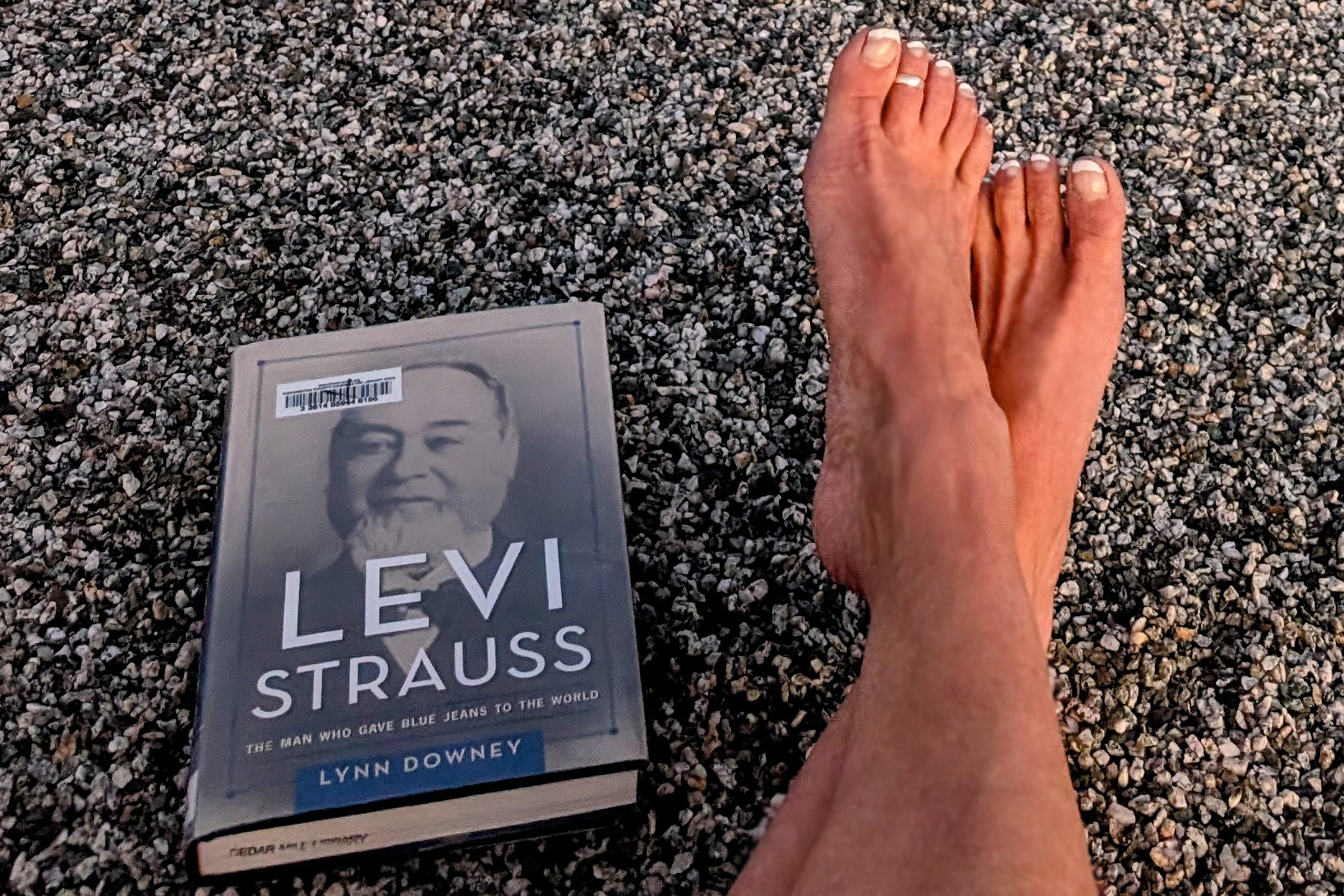

But as I tried to imagine his response, it suddenly hit me: I had no idea what Levi Strauss even looked like. I’d been saying hi for twenty years, but I only knew Levi Strauss as a label, not as an actual human being. I apologized for my manners and promised him I would fix that.

I bought the only biography ever written about Levi Strauss, expertly crafted by historian Lynne Downey. Most of his records had been destroyed in the fires after the earthquake, so the book itself was a remarkable feat and an excellent read. But I was in for another surprise.

Levi Strauss was eighteen when he immigrated from Buttenheim, Bavaria, to New York to join his brothers in their dry-goods trade. In 1853, he was sent west to run the San Francisco division of the family business. And then my jaw dropped as I learned the rest.

The Stitch That Changed the World

Levi Strauss did not invent jeans. He was the man who knew how to mass-produce them. The real MVP and creator of riveted pants was somebody else entirely, and I’d never heard his name.

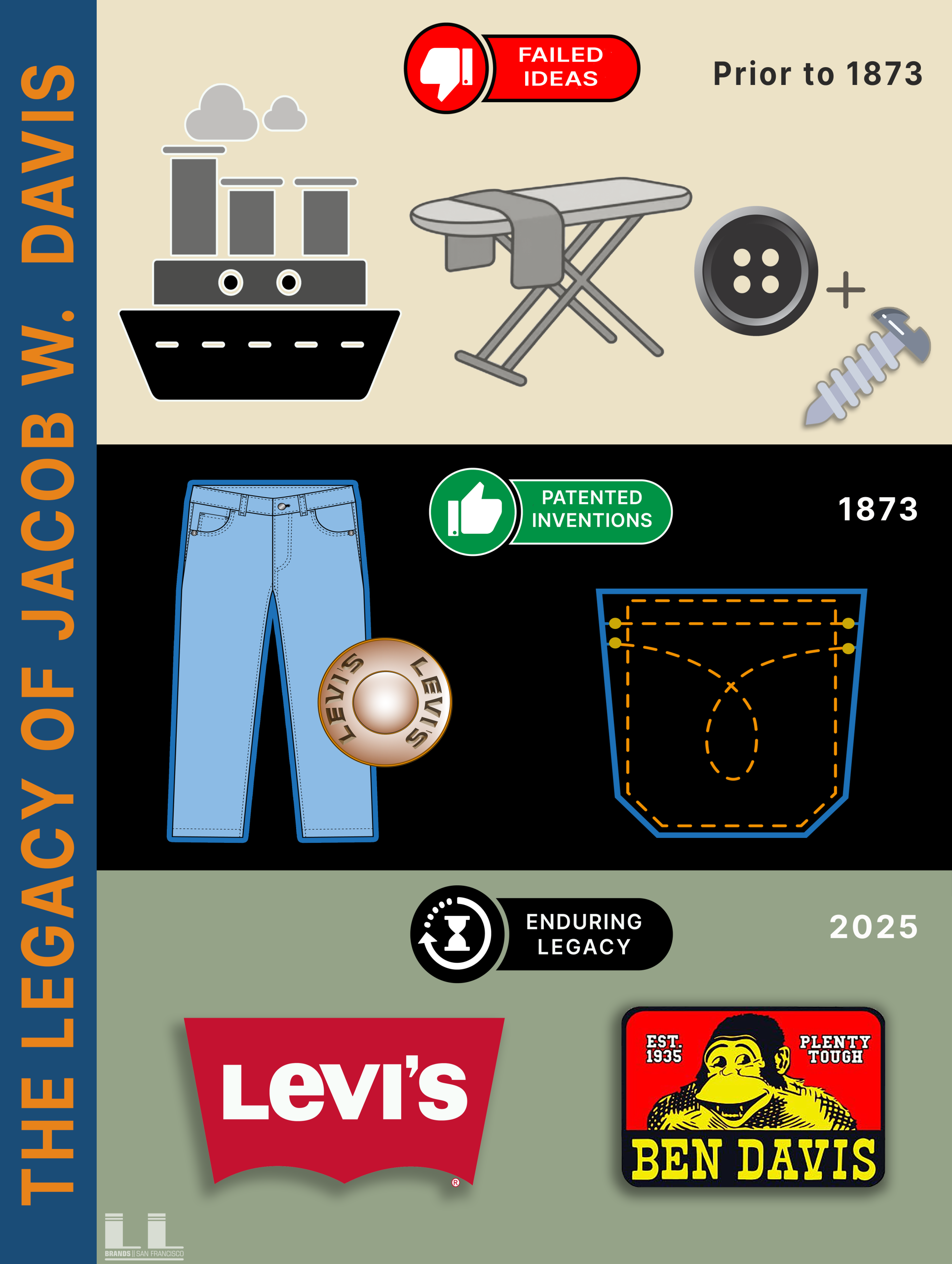

Jacob W. Davis, or J.W. as he liked to be called, was a tailor from Riga, Latvia, who immigrated to the United States in 1854 at the age of twenty-three. He traveled across the U.S. and Canada looking for work, filing patents along the way for a canal steamboat, an ironing board, and a button that fastened with a screw, but nothing took.

Eventually, he returned to tailoring and opened a shop in Reno. In 1871, a woman came in and asked him to make pants for her husband—but she had a special request: make them extra strong.

Until then, pockets often tore off when people carried tools, and nobody thought twice about it. But J.W. had been sewing horse blankets and had some rivets nearby, so he had the notion to use them as reinforcements. Pockets never fell off again.

The pants were a huge hit, but after a year, he couldn’t keep up with demand, and others began to copy the idea. He applied for a patent, but it was rejected, likely due to his poor English. He wrote a letter to Mr. Strauss, who may have been his fabric supplier, seeking financial backing. They became partners: Mr. Strauss scaled distribution while J.W. ran production. He also invented the orange stitch design that became their signature look. They each stayed at the company for the rest of their lives.

Both men were extraordinary in their own right. Strauss became thoughtfully engaged in politics, using his influence to push for the kind of civic reform that would help to build an early San Francisco. And J.W. helped me realize that I was Jacob Davis in the equation in need of a Levi Strauss. Because in cannabis, where policies can literally shift overnight, timing is often the only real difference between progress and prohibition.

While Mr. Strauss never married or had children, J.W.’s son and grandson went on to found the Ben Davis Clothing Company in 1935, a San Francisco workwear brand still in operation today.

Ghosts in the Fabric

Recently, as the summer fog rolled into San Francisco, I ordered some Ben Davis beanies to stay warm and needed to spend another $3 to hit free shipping. I spotted something called “suspender buttons” for $4 and bought them. When the package arrived, I poured out the contents of a small bag into my palm, and I could hardly believe my eyes.

I was holding buttons that fasten with a screw. J.W.’s failed invention had managed to time-travel more than 150 years and land in my lap, demonstrating firsthand how far an idea can go once it’s been put into the right pair of hands.

It’s a powerful insight that applies to the plant, too. This is the moment when the story of cannabis gets rewritten, and finally course-corrects after a very long and most regrettable misunderstanding. Pairing ideas with action today will steer the innovations that matter tomorrow, ensuring that cannabis finds its way back to its rightful place in history. Because healing isn’t just the goal—it’s the plant’s legacy.

As luck would have it, Jacob W. Davis resides at the same cemetery as my father and Mr. Strauss, so I visit JW now, too. I leave a stone on his grave, and I always make a point to tell him, “Thanks for the jeans.”

All images courtesy of the author, LL St. John with featured image by Banjo Schmarino.

This article is from an external, unpaid contributor. It does not represent High Times’ reporting and has not been edited for content or accuracy.