“An adjustment…is generally warranted if the defendant’s primary function in the offense was plainly among the lowest level of drug trafficking functions, such as serving as a courier.”

By Kastalia Medrano, Filter

New amendments to federal sentencing guidelines will put less of an emphasis on the quantity of drugs someone was charged with, and give more consideration to the scope of their role in the overall drug distribution chain. The United States Sentencing Commission implemented the amendments November 1.

Federal sentencing is calculated using a deeply convoluted scoring system that assigns a base offense level (BOL) between 1 and 43, according to how serious a conviction is perceived to be. For drug-trafficking, this is determined partly through a Drug Quantity Table that uses the number of grams involved to assign a BOL that—prior to the new amendments—could be between 6 and 38. But about two out of three people were being sentenced using a BOL of between 30 and 38.

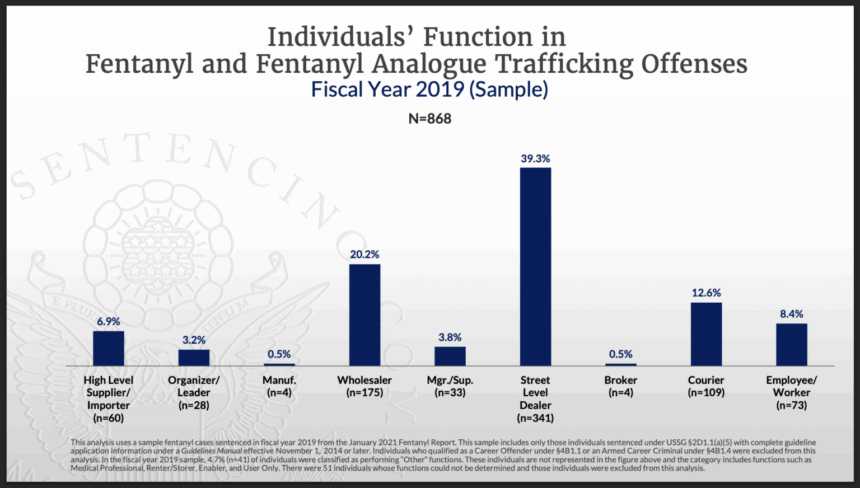

The fixation with quantity as the biggest factor in how serious each case made it easy to prosecute local distributors as if they were high-level members of drug trafficking organizations. Neighborhood sellers who might only deal in relatively small quantities could still be assigned a BOL for much larger quantities, if the number was measured over a long period of time or manipulated in other ways.

The length of someone’s prison sentence also depends on other factors like prior convictions, but a higher BOL correlates to a longer sentence. For a BOL of 37 or higher, the upper end of the sentencing range can be life in prison, depending on the person’s criminal-legal history.

Now, BOL will be capped at 32 for people determined to have a “mitigating role” in the violation—meaning those at the lower end of the supply chain—and the USSC is supporting a broader application of that standard. A BOL of 32 means a sentencing range of roughly between 10 and 22 years.

“An adjustment…is generally warranted if the defendant’s primary function in the offense was plainly among the lowest level of drug trafficking functions, such as serving as a courier, running errands, sending or receiving phone calls or messages, or acting as a lookout,” state the guidelines. “[Or] if the defendant’s primary function in the offense was performing another low-level trafficking function, such as distributing controlled substances in user-level quantities for little or no monetary compensation or with a primary motivation other than profit.”

Primary motivations other than profit could include personal relationships, or being threatened or coerced. The USSC is still considering whether to apply the adjustment retroactively.

Another amendment applies to fentanyl-related substances specifically. In 2018 the USSC added a four-level sentencing enhancement for cases involving fentanyl or fentanyl analogs, if the person convicted was found to have “knowingly misrepresented” a substance as not containing fentanyl. Then in 2023 it added an alternative enhancement of only two levels if the level of awareness could be characterized as “willful blindness or conscious avoidance of knowledge,” which implies less intent. Now, the two-level alternative can be applied for “reckless disregard,” which is intended to make it more widely used in place of the four-level enhancement.

Not all proposed amendments were adopted. The USSC had been poised to make long-awaited changes to the sentencing enhancements for methamphetamine, which unlike almost all other banned substances is criminalized according to purity, rather than quantity. More than 80 percent of drug-trafficking cases with a BOL of 38 involved meth.

In 2024 the USSC published its first analysis meth-related convictions in nearly a quarter-century, which showed that they make up close to half of all federal drug-trafficking convictions and are the most likely to involve mandatory minimum sentences.

In April, when the commission voted to adopt the other 2025 amendments, it never voted on that one.

This article was originally published by Filter, an online magazine covering drug use, drug policy and human rights through a harm reduction lens. Follow Filter on Bluesky, X or Facebook, and sign up for its newsletter.