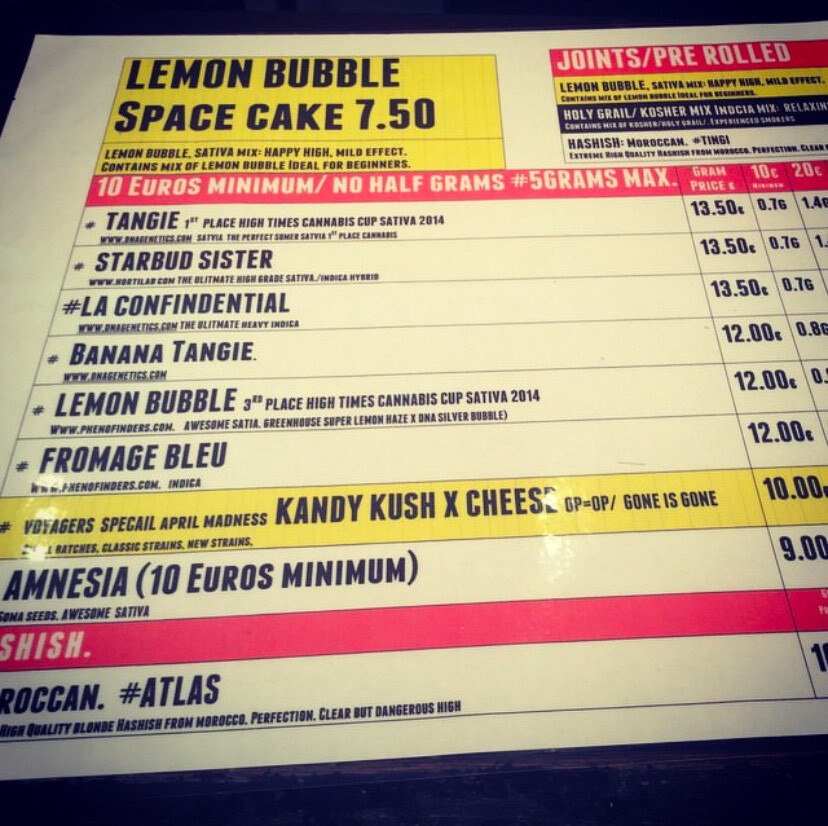

I still keep, in my phone’s notepad, the list of strains I smoked and the coffeeshops where I scored them—a personal archive of Amsterdam’s green bounty. I made that pilgrimage in April 2015, spending fifteen days on my own with one simple mission: hit as many coffeeshops as I could and, of course, do what stoners do best—smoke until our terpy desires feel fully satisfied.

By then, it had been nearly forty years since the Dutch legalized possession and quietly tolerated cannabis sales, and Amsterdam was still the stoner’s holy land. Sure, 2015 wasn’t the wild, golden haze of the 1990s, when coffeeshops multiplied on every corner. But the weed was still world-class. I rolled through shops sampling varieties of haze, different types of kush, and creamy slabs of hash that melted like butter on toast.

What I knew was this: on the streets, I could only carry five grams. Inside a coffeeshop, the place itself could hold 500 grams—and that number included whatever was baked into space cakes, and even the clients’ stashes.

And that’s where the Amsterdam Paradox really hit me. How could these shops keep the shelves stocked, if the law said nobody could legally move more than five grams at a time? The math just didn’t add up. The Dutch had a name for it: the Backdoor Policy. Up front, the law lets you buy and smoke. Out back, it pretends the supply magically appears. It’s the famous Grey Area, a foggy space where legality and illegality blur together, and where Amsterdam’s cannabis culture has been living for decades.

Between sips of coffee or tea, I’d think about how all of this came to be—this strange, beautiful experiment called the Dutch coffeeshop. What started as a loophole in the law had turned into a culture so unique that people like me would cross oceans (as I did when I left Brazil) just to sit at a sticky wooden table and be part of it.

The Dutch Tolerance Policy

The story of the prohibition of drugs in the Netherlands starts way back in 1919, when the country passed the first Opium Act, banning opium and cocaine. Marijuana prohibition only came in 1928, when lawmakers moved to block the import and export of the plant. In 1956, production, possession, and sale of cannabis were criminalized—but with a strange twist. The law only defined cannabis as the “dried tops of the plant”. To put it simply, just the buds were illegal.

Cannabis culture itself arrived in the Netherlands through the back door: jazz musicians and underground artists in the 1950s, followed by the explosion of youth counterculture in the 1960s. Hashish, smuggled in from North Africa, became the fuel of choice for the growing army of European hippies. By the mid-1970s, Amsterdam’s tolerance was already making headlines. The Dutch Health Minister, Irene Vorrink, had even floated a legalization bill in 1972, backed by her Socialist Party. Though the politics didn’t line up.

The High Times magazine edition of March 1975 was already picking up on a uniquely Dutch agent in the fight for cannabis freedom. An article told the story of the Lowland Weed Compagnie, a little operation run by activists Jasper Goetveld and Kes Hoekert—veterans of the Dutch Provo movement, the countercultural crew that had been shaking up Amsterdam since the 1960s. They saw the loophole in the law: buds were illegal, but seeds and young plants technically weren’t.

Goetveld and Hoekert started selling seeds and starter plants, turning their company into the first cannabis seed supplier in the Netherlands. It wasn’t a seed bank in the modern sense—they weren’t breeding or stabilizing new genetics—but it was revolutionary all the same.

Then came the real drug crisis: heroin. In the early 1970s, Dutch teenagers were getting hooked in alarming numbers, and suddenly the debate in parliament wasn’t about hippies smoking joints, but about stopping kids from overdosing. Thus, in 1976, the government revised the Opium Act with a bold idea: split drugs into two categories—hard drugs (heroin, cocaine, LSD) and soft drugs (cannabis). Cannabis was recognized as risky but nowhere near as destructive as the hard stuff.

The reform slashed penalties: possession of up to 30 grams of weed was downgraded to a minor offense, carrying at most a month in jail. It was a strategy—a way to keep cannabis users away from the heroin scene, to stop a generation from sliding deeper into addiction. The foundations of the Dutch “tolerance policy” were born.

The Coffeeshop Culture

The law didn’t predict how cannabis would be sold, and it certainly didn’t foresee the rise of the coffeeshop culture. So the Dutch weed market grew organically, shaped by the underground before the government ever caught up. In the 1960s, cannabis was traded on the streets of Amsterdam by young countercultural rebels; while in the 1970s, just before the 1976 law reform, hashish especially became the domain of the so-called house dealers.

These were semi-clandestine sellers, operating from youth centers, clubs, or squats—tolerated by their communities. So youth centers began appointing hemp sellers, and coffeeshops soon followed, giving cannabis its own safe channels apart from heroin and cocaine.

By 1979, the Dutch government realized that criminally prosecuting small-time cannabis sales did more harm than good. So they drew up guidelines, the now-famous AHOJ-G rules: no advertising (geen reclame), no hard drugs (geen harddrugs), no public nuisance (geen overlast), no minors (geen jeugdigen), and no large quantities (geen grote hoeveelheden).

That framework set the stage for the 1980s, when the coffeeshop culture truly bloomed. As long as they played by AHOJ-G, coffeeshops could exist in plain sight, rolling the underground into something halfway official.

The popularity of Amsterdam as a marijuana haven was reported in the High Times magazine of October 1982 in a piece called “Amsterdam: An Inside Look at the New Jerusalem of Drug Culture”, written by William Levi (a longtime resident). In his section Hashish Heaven, Levi explained it plainly: “If you say you’re from Amsterdam, the automatic response anywhere in the world is: ‘Ah, Amsterdam, you can smoke there.’”

And smoke they did. At the Melkweg, queues of forty people or more lined up for Afghani, Lebanese hash, Nigerian weed, or the latest space cakes. House dealers moved serious volume—rumors of ten kilos gone in a single weekend. The cannabis trade grew organically, shifting from youth centers to improvised “coffeehouses,” where the AHOJ-G rules (no ads, no hard drugs, no minors, no nuisance, no big quantities) kept things technically under control.

One of the first was Coffeeshop Rusland, which opened in 1977 near Dam Square. It looked like a café—coffee, tea, cakes—but in the back sat a dealer with pre-weighed bags, calling out what was on offer. Then came The Bulldog, with its white bulldog mascot lounging out front. Today it’s a tourist empire, but back then it was just another DIY space where the culture was taking root. Other shops followed. By 1982, Levi counted around thirty active cannabis spots across Amsterdam, many unmarked, their presence betrayed only by the sweet smell of smoke drifting out of open windows.

When the Cup Became a Culture

By 1988, Amsterdam’s tolerance had created the perfect stage for the very first High Times’ Cannabis Cup. What started as an invite-only gathering soon opened to the public, drawing thousands of smokers eager to experience a city where they weren’t criminals. By the mid-1990s, Amsterdam had already become the pilgrimage site for stoners worldwide. Coffeeshops became not just places to buy weed but symbols of an alternative way of life. And for a generation raised under prohibition, that shock—the moment weed culture was suddenly visible, normal, and celebrated—was almost as powerful as the first hit itself.

The numbers were staggering: by 1995, there were somewhere between 1,100 and 1,500 coffeeshops across the Netherlands, most clustered in the capital. For a country that had once insisted this was about harm reduction, it was beginning to look more like an unregulated green gold rush.

So the government pulled the brakes. In 1996, they released a report with a sober title — “Drug Policy in the Netherlands: Continuity and Change” and put the coffeeshops under new rules. Age limits were standardized at 18 (in some places it had been as low as 16). The personal possession limit dropped from 30 grams to 5 grams. Shops could keep no more than 500 grams in stock at a time. Alcohol sales were banned outright. And, perhaps most importantly, municipalities were given the power to license coffeeshops, or to sweep them out entirely. By the 2010s, nearly 70% of Dutch municipalities had adopted a “zero tolerance” stance, meaning they could close coffeeshops even if they followed every rule.

The impact was undeniable. From a peak in the mid-90s, the number of coffeeshops slid steadily downward: 813 in 2000, 729 in 2005, 660 in 2010, and 573 by 2016. The latest counts suggest that the number hasn’t budged much since.

Still, the culture didn’t just disappear, and neither did the Cannabis Cup. Through the 2000s, the Cup thrived. In 2007, the 20th Cup was a spectacle, and High Times editor Steven Hager leaned into its ritualistic vibe, writing about the “spiritual rights” of cannabis. He had no clue that the Cup, which started with just three seed companies, would explode into an international institution.

Tolerance on Trial

Nevertheless, even the Cup couldn’t dodge the shifting winds of Dutch politics. In 2012, the national government floated the dreaded wietpas—a “weed pass” that would limit coffeeshops to Dutch residents only, essentially shutting out the tourists. Border cities like Maastricht embraced it. Amsterdam pushed back hard, resisting what they saw as economic and cultural suicide. The city knew its identity was on the line.

In the year of the 27th Cannabis Cup, 2014, tensions hit a breaking point and the Cup was nearly strangled out of existence. Justice Minister Ivo Opstelten forced organizers to agree to absurd conditions: no solvent-based concentrates like BHO, no indoor smoking, 5-gram possession caps, invasive security checks, no freebies, no shared vaporizers.

Even after all that, police threatened to raid the event an hour before the doors opened. The Hemp Expo was canceled on the spot. The Cup limped on with coffeeshop tours, panels, and late-night reggae shows. The age of easy tolerance seemed to be ending.

Inside the community, the frustration was palpable. Coffeeshop pioneers like Derry Brett of Barney’s bristled: “What the government needs to do is let us grow legally and establish quality control. Otherwise, people’s health is at risk.” There’s no legal supply chain, no quality control, no guarantees against contamination.

High on the Paradox

The following year, I was back—curious, skeptical, and chasing a proper 4/20 in Amsterdam. After the chaos that had rattled the Cannabis Cup the year before, I wanted to see if the city still had some spark, some kind of celebration. What I found was modest: a haze gathering in Vondelpark, with Bulldog promoters handing out papers and filters like party favors.

But Amsterdam always has its surprises. Over at Grey Area, a legend in its own right, someone sparked a 30-gram joint and passed it around the shop. I managed to snag a hit or two. The culture was still alive.

Later, I ended up on a quiet bench, baked to perfection, watching the endless ballet of bikes weaving through the straats. My mind wandered: how long could this last? How long would tourists still be able to walk into a coffeeshop and feel this strange Dutch gift of freedom? Amsterdam’s Paradox was sitting right there with me—the joy of puffing openly, paired with the knowledge that politics could snuff it out at any moment. Still, Dutch tolerance has a way of surviving every conservative curveball. They’ve tried to lock tourists out, but the vibe in Amsterdam always finds a way to endure. And me? I’m still out here daydreaming about the chance to experience a Cannabis Cup in the city — to finally feel that mix of smoke, music, and history rise together in the only place that could’ve birthed it.

All photos courtesy of Caio Zanin.

This article is from an external, unpaid contributor. It does not represent High Times’ reporting and has not been edited for content or accuracy.