Presidential elections in Costa Rica are scheduled for February 1, 2026, and we’re looking at quite a broad landscape. Amid fragmentation and indecision, Costa Ricans will have to choose from a vast array of candidates. Some of them have publicly stated their positions on cannabis legalization. Since 2022, Law 10.113 has been in effect, regulating weed exclusively for medicinal and therapeutic purposes. This law also authorizes the food and industrial use of hemp. However, recreational or adult use remains illegal in the country, and the Narcotics Law still criminalizes personal possession. Now, following recent attempts to legalize and regulate recreational marijuana, the issue has returned to the public spotlight.

According to data from the Institute on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, an agency attached to the Costa Rican Ministry of Health, a survey on psychoactive substances shows that pot use has been increasing since 1990. “Whether we like it or not, that is a reality we cannot deny,” says Juan Carlos Hidalgo, candidate for the Social Christian Unity Party.

“Cannabis use exists in Costa Rica, but prohibiting its sale leads to demonization by some sectors, and the discussion remains dominated by criminalization. There is no secular, scientific, and non-moralistic educational policy regarding cannabis use, so the context is still slow,” adds David Hernández Brenes, candidate for the Working Class Party.

Lately, there has been an increasing police pressure and security operations have focused on confiscation. “The user is often criminalized. Use is not prohibited; its sale and cultivation are,” notes Ariel Robles Barrantes, a candidate for the Broad Front.

Now, what do the candidates who have taken a public stance actually propose? “Adult use cannabis, or other soft drugs, should be a personal decision in which state action has allowed each person to decide on their use in an informed, scientific, and secular manner, without fear of a punitive or moralistic attitude from the state. Use should be conscious of all the aspects involved in these substances,” says Hernández Brenes.

In that sense, Hidalgo also believes that weed “should be a substance whose recreational use is legal and, of course, regulated with public health criteria that guarantee the protection of the population, especially minors.” And in the case of Robles Barrantes, he sees legalization as a “benefit.” First, he asserts, it would be positive in “taking the business away from drug cartels.” He says: “Today, in our country and in any Latin American country where cannabis use is not regulated, it is truly left to its own devices, and it is the illicit business that ends up profiting.” From there, he proposes generating resources for the State to manage. “These resources can be invested in education, health, and security, and this, in turn, generates employment,” Robles Barrantes points out.

However, in Costa Rica, religious and ultraconservative sectors tend to oppose this polarizing issue, highlighting its complexities and tending to create divisions. But despite this resistance, the debate is on the public agenda, and part of the electorate is asking various political groups what their candidates’ positions are on this topic.

Robles Barrantes immediately defends the possibility of debate and acknowledges that it is “especially the younger generation” who have “most strongly defended the argument for regulating cannabis use.” In 2023, Robles Barrantes caused a media stir after a confession: “Just as Barack Obama said during his campaign, I also said that I had used weed at one point, but that it didn’t make me a bad person, nor did it make me a criminal. I did it to try to fight the stigma.”

Hidalgo, for example, knows that this discussion requires tools to “make an informed decision.” In his words: “The risks of problematic use of this and many other substances must be made clear.”

Robles Barrantes returns to the point: “We require responsible regulation, understanding that it also generates a social impact and that there are people for whom cannabis use can be problematic. Therefore, we must create a support program and provide assistance to families.”

Among the electoral platforms, Hernández Brenes, candidate for the Working Class Party, focuses on unemployment, poverty, public health, education, and housing. “We propose a process of socializing businesses and implementing economic planning with a government based on workers’ assemblies,” the candidate announced, a proposal that sparked controversy on social media and in the press. “We propose a series of policies to end the carnage that exists in workplaces,” he continued.

Meanwhile, Juan Carlos Hidalgo, candidate for the Social Christian Unity Party, seeks to “level the playing field.” His main proposal focuses on addressing the concentration of “great benefits.” In his words: “Leveling the playing field means bringing those benefits to all Costa Ricans and allowing those who go to work every day and deal with taxes, insecurity, costs, red tape, and a lack of infrastructure to thrive.”

And in the case of Ariel Robles Barrantes, the Broad Front candidate, he intends to return to investing in education and give his potential term a focus on security, not just police presence, but preventive measures. He also proposes social investment for the development of housing, schools, health centers, and public spaces. “An approach that can impact people’s quality of life,” he explains.

Seeking to tap into widespread discontent with the political class, Hernández Brenes plans to reap benefits where abstention and apathy are prevalent. “We expect to attract more and more people to our proposals so that we can develop an alternative that radically changes the course of the country and focuses on an economy based on satisfying the needs of the working class,” he states.

Hidalgo is confident that Costa Ricans, upon learning about their proposals and hearing them debated, “will realize that we are the best alternative.” He states: “We don’t intend to deny or destroy what’s good about us, but rather we seek to expand it.”

And Robles Barrantes, with some polls in his favor, hopes to reach a second round of elections to challenge the current government. “We seek to govern with a different perspective, with a social focus, that recognizes the dignity of work, that strives to reduce the workday, and so that we can once again have a model of education, health, and security as the foundation of one of the most solid democracies in all of Latin America,” he concludes.

The debate on cannabis in Costa Rica has become an unexpected driving force in these presidential elections. Even with the burden of stigma and conservative reactions, a considerable sector of the electorate is forcing the candidates to move beyond the gray area and present their vision on regulation. Thus, on February 1, 2026, Costa Ricans will elect a new president. Will the next government be the one to remove the criminal label from weed and incorporate it into the tax system? The answer lies in the ballot box.

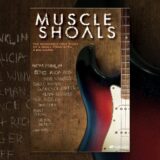

Photo by aboodi vesakaran on Unsplash