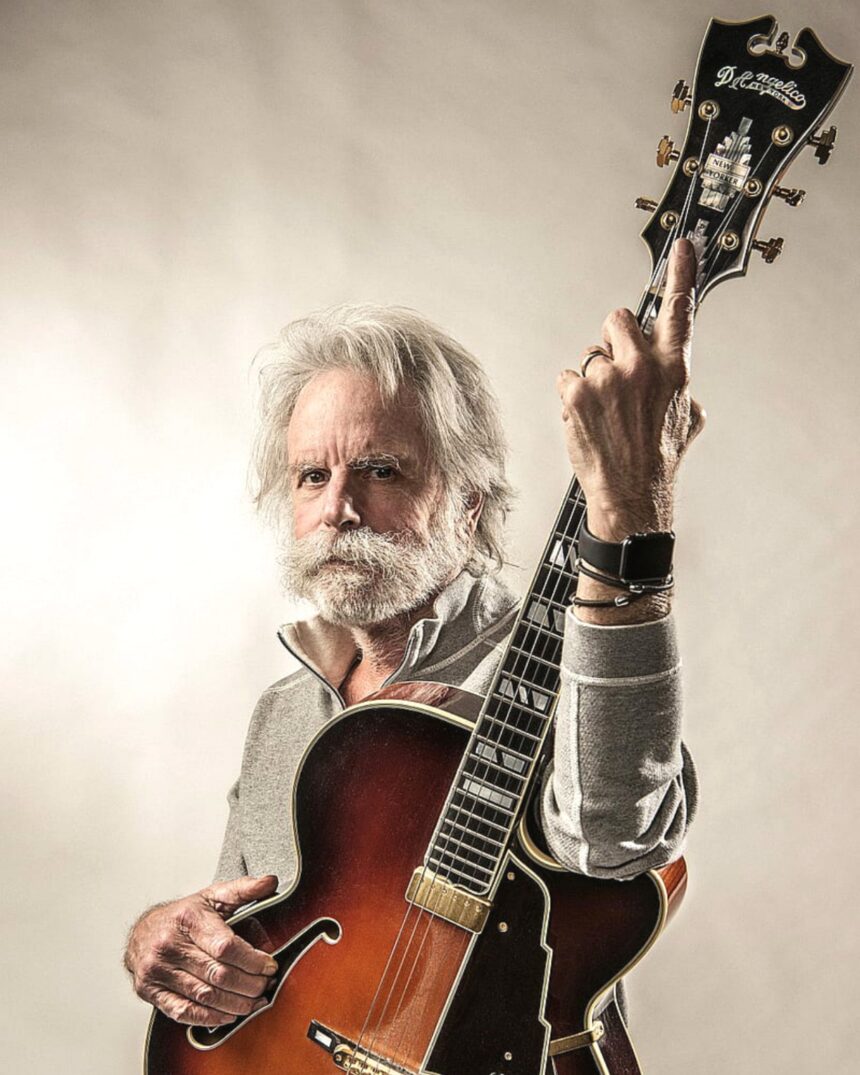

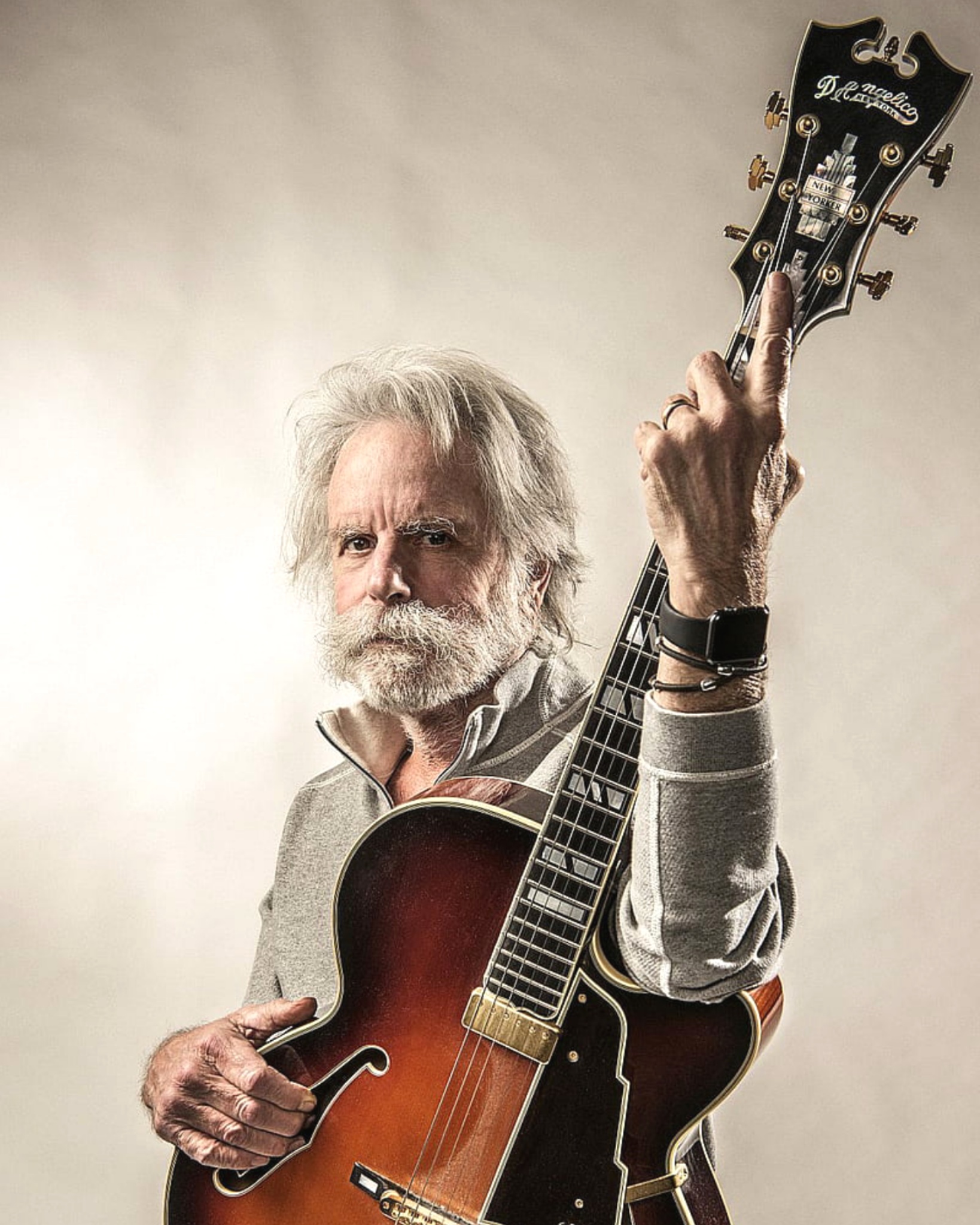

This piece is, first and foremost, a tribute to Bob Weir, and to a life spent creating, persisting, and refusing stasis. It reflects on the influence of an artist whose impact was not confined to charts, movements, or moments, but unfolded over decades through presence, continuity, and an uncommon willingness to keep going. Weir’s work, approach, and longevity shaped not only a musical lineage but a way of participating in culture that favored openness over control and evolution over preservation.

Viewed through that lens, the story also traces the evolution of cannabis from informal social practice to regulated commercial enterprise, and the tensions that transformation has produced. It considers how cannabis culture was sustained long before it was monetized, how community-based norms differ from institutional frameworks, and how scale, capital, and compliance can both legitimize and distort what they seek to protect. Interwoven are reflections on risk, longevity, decentralization, and influence without authority, while using Bob Weir’s path as a reference point for understanding what the cannabis industry has gained, what it has compromised, and what lessons may still be recoverable.

******

“The bus came by and I got on—that’s when it all began.”

Before the Law Caught Up With the Culture

Before cannabis was regulated, branded, taxed, and debated in committee rooms, it lived where Bob Weir lived: in parking lots and passenger vans, in half-lit arenas and muddy fields, passed hand to hand with the same unspoken trust as a lighter or a lyric. For the Grateful Dead, cannabis wasn’t a cause or a commodity, it was part of the shared language of curiosity, patience, and community. Bob Weir didn’t preach it. He inhabited it. And in doing so, he helped normalize a culture long before the law ever caught up.

It was 1963, and Bob Weir was sixteen years old when he met Jerry Garcia at Jerry Morgan’s Music Store in Palo Alto, California. Jerry was playing the banjo; Bobby heard the sweet sounds. Bobby walked in, leading to a marathon jam session and the start of their musical journey together. Bob was just a kid with a guitar and an instinct. That accidental meeting didn’t just spark a band; rather, it ignited a culture, a community, and a way of thinking that would ripple through American music, counterculture, and cannabis history for decades.

The Grateful Dead didn’t arrive fully formed. Neither did the movement that grew around them. It was improvised, communal, messy, joyful, and defiantly human. Bob Weir would become one of the most singular rhythm guitarists ever to stand on a stage; his rhythm guitar playing is isolated in numerous online recordings; take a listen…mind-blowing. He was angular, conversational, intentionally off-center. While he often dominated the stage, he didn’t dominate the music. He challenged it. He complicated it. He kept it alive.

Over more than six decades, Bob Weir never stopped. The band kept playing on.

The Long Road After Jerry

The Grateful Dead. Kingfish. Bobby and the Midnites. RatDog. Weir & Wasserman—anchored by the late great Rob Wasserman on stand-up bass. Dead & Company. Wolf Bros. Orchestral collaborations. Solo tours. Side projects that became lifelines. Once asked why he always had so many side projects, Bob simply said, “Because I love to play.” While others slowed down, retired, or calcified into nostalgia, Weir stayed restless. He toured relentlessly. He experimented openly. He trusted the road.

And when he passed, the music didn’t end, it won’t end, but the silence hits hard.

Bob Weir wasn’t just a legend to me. He was my compass.

I didn’t realize it at first, but I modeled so many parts of my life after him. Bob was a man of few words. Quirky. Aloof. Sometimes misunderstood. Often underestimated. But always himself. And always moving forward. Bob mused romantically about being a cowboy, as did I when I moved to Wyoming in 1998; this is the source of inspiration for so many Dead cowboy tunes. I once wrote a legal article titled “Victim or the Crime,” focused on hate crime legislation. My professional writing, including my Forbes columns over many years, always includes dedicated Grateful Dead lyrics. We named our daughter, Cassidy!

When Jerry Garcia died in 1995, I was just starting to appreciate Grateful Dead tours and just beginning to understand how deeply cannabis, music, and community were braided together in the Dead universe. At the time, the Dead were already a thirty-year institution, but the scene felt timeless. Parking lots turned into temporary cities. A traveling carnival. A shared hallucination built on music, curiosity, kindness, and cannabis. Massive drum circles under overpasses with balloons bursting and nitrous tanks hissing in the background. It was a rainbow full of sound, with fireworks, calliopes and clowns. Everybody’s dancing.

The music was electric. Cannabis smoke drifted easily and unapologetically through the air. The crowd was multigenerational, with eight-year-olds and eighty-eight-year-olds dancing side by side. The culture was welcoming and alive. It welcomed my friends and me. After attending Catholic school for so long, it opened us up.

That summer, with my buddies, Lew and Jason, I drove from home in South Jersey to RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. for a Dead show—June 24, 1995. Cannabis fueled our drive down I-95. This wasn’t a statement or a rebellion; it was simply part of the atmosphere. At the time, we mostly knew the studio albums, which, as any Deadhead knows, is not where the band truly lived. The Grateful Dead were a live organism.

None of us had a reliable car. I borrowed my Dad’s Mazda 929—a massive, plush four-door sedan built for comfort, not rebellion. We loaded it with CDs and Dead show cassette recordings. Tape trading was everything back then. You’d visit the Woodstock Trading Company in South Jersey, request shows that you picked from the book, DeadBase, drop off blank tapes, and wait weeks. When those tapes came back, it felt like treasure.

The Dead encouraged it. They created taper sections. They allowed recording. Music was meant to travel, to be shared, not controlled; the same quiet social contract that governed cannabis in the Dead world: communal, trust-based, and defiantly outside permission structures. Music was meant to travel, to be shared, not controlled. Some people built entire lives around those tapes. In hindsight, that philosophy mirrored cannabis culture perfectly, as it was decentralized, trust-based, and community-driven.

Driving south on I-95, buses and semis flying past us, we listened, and we argued.

Who really was this boisterous, deep-voiced frontman? The one who sounded cocky. Abrasive. Maybe even obnoxious. Who did he think he was? Not Jerry.

Back then, the jury was out on Bob Weir.

That wasn’t uncommon. Deadhead culture had a long tradition of skepticism toward Bobby. The short shorts. The swagger. The songs that didn’t always land. I remember parking-lot T-shirts featuring a block of Velveeta cheese that read “Cheese it up, Bobby.” Bobby was often perceived as cheesy; as rockstar Bobby.

Jerry, by contrast, was untouchable. He was the gentle guitar wizard, the spiritual center. In comparison, Bobby seemed brash.

And then the show started.

“Jack Straw” opened.

By the end of that night, everything we thought we knew was wrong. We returned to Georgetown, where we were staying, our skin stained green from the $5 tie-dyes we’d bought in the parking lot. We dove deeper into the Bob Weir songbook.

We listened differently. We leaned in. We started chasing Bob Weir songs—deep cuts, risky ones, sometimes flawed ones. “My Brother Esau.” “Picasso Moon.” “Festival.” Even the misfires mattered. Bob always added something. He never diluted the band, even when the audience wasn’t ready.

During a concert, the Dead had a rhythm where there was a Jerry song, Bobby song, back and forth. Not a rule, just the way it most often unfolded. And the philosophy of the Dead was one where everyone got to shine; everyone got to play lead, in effect. This was the Bobby mentality. Slowly, Bobby won us over. Eventually, for many of us, he became the anchor.

This era followed In the Dark, the band’s first true commercial success. “Touch of Grey” cracked the pop charts. And if you want to understand why Bobby caught heat, just watch the online video for “Hell in a Bucket.” That explains a lot.

Then Jerry died.

For many of us, it felt like the end. And unfortunately, for many of us, it was just about the beginning of our love for this band. After all, it was a band beyond description. Were they ever here at all?

The Music Never Stops

Around that same time, my father remarried. At the wedding, my Uncle Jimmy mentioned a band called RatDog—and how much he loved Bob Weir. Who knew? RatDog was Bob’s new band, and it was different. A horn section. A new groove. Same soul. It brought the road back to life. Many of us fell in love…again.

Show after show. City after city. As many as I could afford as a student. We chased Bob Weir around the country. I even formed my real estate company, Weir Here LLC. W-E-I-R became my four-digit PIN.

Bob stayed on the road. Always. It’s been said that no one has played more live concerts than Bob Weir. Whether or not it is literally true, no one has played more large-scale shows over more decades with more consistency.

The music never stopped.

RatDog album Evening Moods remains one of the most underrated albums of that era. It is brilliant from start to finish. You won’t find it easily on major streaming platforms, but it lives on YouTube. Like much of the Dead universe, it survives because people care enough to keep it alive.

In April 2008, RatDog closed its Spring tour at the Beacon Theatre in New York City. I flew back from law school in the West to meet friends from New York and Philadelphia. Three nights. Transcendent. Those setlists can be found on setlist.fm —go look it up. Fantastic!

After the last show of that run, my friends and I walked out buzzing, drifting north toward 72nd and Amsterdam on the Upper West Side. Standing in a circle outside a bar, decompressing, smoking, telling stories. A Lincoln Town Car pulled up. The door flew open. A man barked something into the back seat— “There will be repercussions,” the man said. He slammed the door, and stormed through our group, inadvertently shoulder-checking my friend Jason.

It was Bob Weir.

He asked to bum a cigarette. We obliged. Turns out the band had rented the back room of that bar for their end-of-tour gathering.

Four Words That Changed Everything

Later, in the men’s room, guess who arrives at the urinal right next to me? Standing shoulder to shoulder at a urinal, I couldn’t help myself.

“Bobby—amazing tour. RatDog is incredible. Please keep playing. You have no idea what it means to so many people.”

Silence.

He zipped up, stepped back, looked me dead in the eye, and said:

“Nothing ventured. Nothing gained.”

And walked away.

Four words.

I didn’t understand them that night. But they followed me.

In 2008, my Philadelphia Phillies won the World Series. That same year, my mother died from pancreatic cancer. I had two young children—four and six. I was working at a prestigious law firm in Denver and deeply unhappy. Every option felt safe. None felt right.

Nothing ventured. Nothing gained.

These four words inspired me to start my own firm—a law firm centered around ‘canna-business.’ Over the next fifteen years, it grew into the first and largest cannabis-only business law firm in the world—the Hoban Law Group.

All from a sentence spoken in a bathroom.

Culture Before Compliance

Now, Bob Weir was never a policy guy. No podiums. No white papers. He didn’t need them.

Some revolutions start in parking lots.

Cannabis culture didn’t begin with licenses, capitalization tables, or compliance manuals. It began with community. The Grateful Dead didn’t market cannabis—they normalized it. Quietly. Organically. Humanly.

The Dead lived defiance rather than preaching it. Their Haight-Ashbury home was raided in the 1960s. That wasn’t a scandal; it was a rite of passage. Cannabis wasn’t branded. It was passed. Shared. Laughed over. Trusted.

Culture always comes before regulation.

Bob’s relationship with cannabis was never performative. In a 1981 interview, Bob once said that “I am absolutely never stoned on stage…I can’t play stoned…,” as Jerry looked on with a wry smile, and a raised eyebrow of disbelief. When Bob spoke about it, it was sideways—through humor, memory, and civic responsibility. Vote. Pay attention. Don’t let outdated laws calcify simply because power is comfortable.

He understood something critical: legitimacy without memory becomes control.

The Dead’s world was decentralized, communal, and improvisational. Today’s cannabis industry is centralized, capital-intensive, and often hostile to the very communities that carried the plant through prohibition. That tension matters.

Bob Weir never positioned himself as an architect of modern cannabis markets. And that absence is telling. Because commercialization is not liberation. Regulation is not justice.

What Bob and the Dead provided was social permission; the kind that makes prohibition untenable long before laws change. They made it impossible to pretend cannabis users were outsiders.

Even “420” didn’t come from marketers or regulators. It came from kids, from Dead-adjacent culture, passed hand to hand as a code. Culture first. Always.

A Legacy That Couldn’t Be Licensed

Today, as cannabis inches toward federal reform and grapples with normalization, Bob Weir’s legacy sits quietly beneath the surface. The plant survived not because it was profitable, but because people loved it, trusted it, and refused to let it be erased.

You can license cannabis. You can tax it. You can regulate it. But you can’t unteach people what they already know.

Bob Weir didn’t walk this road alone. Every long strange trip has its translators. These were the people who turned music into language, instinct into principle, and culture into something durable enough to survive the future. For the Grateful Dead, one of those translators was John Perry Barlow: lyricist, digital freedom pioneer, and Bob Weir’s close friend and collaborator.

I went to law school in Wyoming, which was Barlow’s home state. And one day at the University of Wyoming, outside of a restaurant, I saw an older man in a long leather coat, arguing intensely into a cellphone. Familiar energy. The same posture. The same refusal to bend.

I was having a smoke. He moved in. Introduced himself. John Perry Barlow. He was in town talking about cyberspace freedom, which is another frontier where culture would once again outrun the law.

Same instinct. Same resistance. Same thread. We talked about the songs and how they never really stop living.

Over the years, there was Dead50 in Chicago, with Phish’s Trey Anastasio. Great shows that I am proud and lucky to have attended. Numerous Playing in the Sand events on the Riviera Maya. Then, Dead and Company with John Mayer began. Ten years and dozens of Dead & Co. shows under my belt soothed my soul. Cannabis brought me to Las Vegas to teach at UNLV’s Cannabis Policy Institute, and I was able to attend numerous Dead Forever shows at the Sphere…what an experience!

And all through 2025, the music definitely lived on. While traveling internationally for my cannabis industry work, I found myself in London while Bob Weir and the Wolf Brothers were playing at the Royal Albert Hall with the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra. In typical Bobby fashion, questionable setlist choices, but an amazing experience. And then there were the final shows in Golden Gate Park—Dead60. These turned out to be his final shows. A fitting end to a career that ended exactly where it began. I was proud to see it all happen live.

Music was meant to travel, and to be shared, not controlled. The Grateful Dead understood that instinctively. It’s why tapers were welcomed, why the music spread hand to hand, city to city, generation to generation. It was decentralized by design, governed by trust, sustained by community rather than permission.

Cannabis followed the same path. Long before licenses, compliance manuals, capitalization tables, and quarterly earnings calls, the plant survived because people shared it. Quietly. Reliably. Outside formal structures. Culture carried it when the law would not.

Today’s cannabis industry has achieved something remarkable: legitimacy. That matters. Regulation, when done right, protects consumers, creates stability, and ensures longevity. But in the rush toward scale and standardization, there is a real risk of forgetting what made legalization inevitable in the first place. Commercialization is not liberation. Regulation is not justice. And an industry that loses sight of its cultural roots risks becoming legal, and hollow.

Bob Weir never tried to control the music. He trusted it to move on its own. That may be the lesson still waiting to be learned.

Bob Weir wanted the songbook—the soundtrack of our lives—to survive three hundred years.

I believe it will.

Eight-year-olds. Eighty-eight-year-olds. Still dancing.

We grew up with Jerry, but we grew old with Bobby. And for that we will all forever be Grateful.

Vaya con Dios, Ace.

Nothing ventured. Nothing gained.

This article is from an external, unpaid contributor. It does not represent High Times’ reporting and has not been edited for content or accuracy.